Colonial Wars |

American Wars |

The Creek War

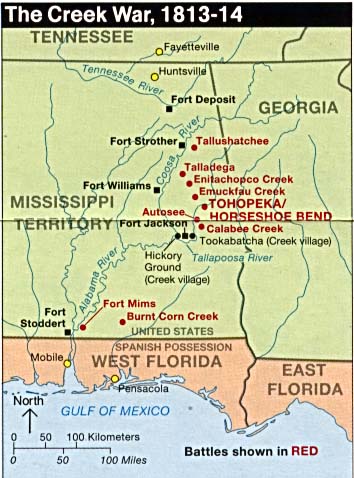

- DATE: 1813-1814

- LOCATION: Southeastern United States

- VICTORY: American

WAR DESCRIPTION:

The Creek War, also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, began as a civil war within the Creek (Muscogee) nation. It is sometimes considered to be part of War of 1812.

Inspired by the fiery eloquence of Tecumseh and their own prophets, the Creeks, known as Red Sticks, sought aggressively to return their society to a traditional way of life. Creek leaders such as William Weatherford (Red Eagle), Peter McQueen, and Menawa, who had been allies of the British during the War of 1812, violently clashed with other chiefs of the Creek Nation over white encroachment on Creek lands and the "civilizing" programs administered by U.S. Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins. Before the Creek War began, the Red Sticks were able to keep their activities secret from the old Chiefs.

In February 1813, a small party of Red Sticks led by Little Warrior were returning from Detroit when they massacred 2 families of settlers along the Ohio River. Hawkins demanded that the Creek turn over Little Warrior and his 6 companions. Instead of handing them over to the federal agents, the old Chiefs decided to execute the murderers themselves. This decision was the spark which ignited the civil war between the Creeks.

The Creeks from the upper towns (Red Sticks) immediately conquered several lower towns with in the Creek Nation. The lower towns had taken steps to assimilate themselves into white culture by raising domesticated animals and farming. The Red Sticks destroyed everything that they perceived to have come from the white man, such as the towns' domesticated animals, pots and pans, and home spun cloths. However, the Red Sticks were not above confiscating the guns and steel blades that they found.

The first clashes between Red Sticks and the American whites took place when a group of American soliders stopped a party of Red Sticks who were returning from Florida on July 21, 1813. The Red Sticks had received munitions from the Spanish Governor at Pensacola. They fled the scene and the soliders began looting what they found. The Creeks, who saw the Americans becoming carried away with their looting, retaliated with a surprise attack. The Battle of Burnt Corn, as the exchange became known, broadened the Creek War to include American forces.

In retaliation, Peter McQueen led an attack, and subsequent massacre, at Fort Mims on August 30, 1813. The Red Sticks' goal was to strike at mixed blood Creeks that had taken refuge at the fort. Despite efforts of some of the Creek leaders, the massacre that left 400-500 dead. Panic spread throughout the American Southeastern frontier, which demanded government intervention. Federal forces were busy fighting the British and the Northern Woodland tribes, so the Southern States had to call up their militias to deal with the threat.

After the battle of Burnt Corn, Secretary John Armstrong notified Gen. Thomas Pinckney, Commander of the 6th Military District, that the U.S. was prepared to take action against the Creeks. Furthermore, if Spain were found to be supporting the Creeks, a strike against Pensacola would be justified. Georgia began its preparations by establishing a line of forts along the Chattahoochee River. This action would protect the frontier and allow time to prepare an offensive.

Brig. Gen. Ferdinand Clairborne, a Militia Commander in the Mississippi Territory, recognized the weakness of his sector on the western border of the Creek territory, and advocated a series of preemptive strikes. However, Maj. Gen. Thomas Flourney, Commander of 7th Military District, continually refused these request and reminded Clairborne that the American strategy in that sector was defensive. Meanwhile, settlers in that region sought refuge in blockhouses.

In response to the massacre at Fort Mims, the Tennessee legislature authorized Governor William Blount to raise 5,000 militia for a 3-month tour of duty. Blount called out a force of 2,500 West Tennessee men under Col. Andrew Jackson. He also summoned a force of 2,500 from East Tennessee under Maj. Gen. John Cocke. Jackson and Cocke were not ready to move until early October.

In addition to the actions of Tennessee, Georgia, and Mississippi, the Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins organized the friendly (Lower Town) Creeks under Maj. William McIntosh to aid the Georgia and Tennessee militias during their battles against the Red Sticks.

At the request of Chief Federal Agent Return J. Meigs, known as White Eagle for the color of his hair, the Cherokee Nation voted to join the Americans in their fight against the Red Sticks.

By count of towns, the Upper Creek constituted about 2/3 of the Creek Nation. Their towns were along the Alabama, Coosa, and Tallapoosa Rivers in the heart of Alabama. Many Creek tried to remain friendly to the U.S. but, after the massacre at Fort Mims, few Americans in the southeast made any distinction between friendly and unfriendly Creeks. The Red Stick force consisted of at most 4,000 warriors, possessing perhaps 1,000 guns. They had never been involved in a large scale war, even with their neighbors.

The Holy Ground (Hickory Ground), located at the junction of the Tallapoosa and Coosa Rivers, was the heart of the Red Stick Confederation. It was about 150 miles from the nearest supply point available to any of the 3 armies. The easiest attack route was from Georgia through the line of forts on the frontier and then along a good road that lead to the Upper Creek towns near the Holy Ground. Another route was north from Mobile along the Alabama River. The most difficult, Jackson's route of advance, was south from Tennessee through a mountainess and pathless terrain.

Outnumbered and poorly armed, the Red Sticks put up a desperate fight from their wilderness strongholds, but valor and the magic of their prophets failed to halt the converging armies. However, because there was no real direction from Washington, D.C. or coordination between the state militias, the war did not end as quickly as it could have. By the end of 1813, 7,000 men from 3 armies had entered Creek territory and killed 800 warriors. However, they had not destroyed the towns which were the center of the Red Sticks power.

Although Jackson's mission was to defeat the Creek, his larger objective was to move on Pensacola. Jackson's plan was to move south, build roads, destroy Upper Creek towns and then later proceed to Mobile to stage an attack on Pensacola. He had 2 problems: logistics and short enlistments. When Jackson began his advance, the Tennessee River was low, making it difficult to move supplies and there was little forage for his horses.

Jackson departed Fayetteville, Tennessee on October 7, 1813. He joined his cavalry in Huntsville, Alabama and crossed the Tennessee, establishing Fort Deposit. He then marched to the Coosa and built his advanced base at Fort Struther. Jackson's first successful actions, the battles of Tallushatchee and Talladega, occurred in November.

However, after Talladega, Jackson was plagued by supply shortages and discipline problems arising from his men's short term enlistments. Cocke, with 2,500 East Tennessee Militia, took the field on October 12. His route of march was from Knoxville to Chattanooga and then along the Coosa toward Fort Strother. Because of jealousy between the East and West Tennessee militia, Cocke was in no hurry to join Jackson, particularly after he angered Jackson by mistakenly attacking a friendly village on November 17. When he finally reached Fort Strother on December 12, the East Tennessee men only had 10 days remaining on their enlistments. Jackson had no choice but to dismiss them. Gen. John Coffee, who had returned to Tennessee for remounts, wrote Jackson that the cavalry had deserted. By the end of 1813, Jackson was down to a single regiment whose enlistments were due to expire in mid January.

Although, Gov. Blount had ordered a new levee of 2,500 troops, Jackson would not be up to full strength until the end of February. When a draft of 900 raw recruits arrived unexpectedly on January 14, Jackson was down to a cadre of 103 and Coffee who had been "abandoned by his men".

Since new men had 60-day enlistment contracts, Jackson decided to get the most out of his untried force. He departed Fort Struther on January 17 and marched toward the village of Emuckfaw to cooperate with the Georgia Militia. It was a long march through difficult terrain against a numerically superior force, the men were inexperienced and subordinate, and a defeat would have prolonged the war. After 2 indecisive battles at Emuckfaw Creek and Enotachopo Creek, Jackson returned to Fort Struther and did not resume the offensive until mid March.

The arrival of the 39th U.S. Infantry on February 6, 1814 provided Jackson a disciplined core for his force which ultimately grew to about 5,000 men. After Blount ordered the second draft of Tennessee militia, Cocke, with a force of 2,000 6-month men, once again marched from Knoxville to Fort Strother. Cocke's men mutinied when they learned that Jackson's men only had 3-month enlistments. Cocke tried to pacify his men, but Jackson misunderstood the situation and ordered Cocke's arrest as an instigator. The East Tennessee militia reported to Fort Strother without further comment on their term of service. Cocke was later cleared.

In mid March, Jackson moved against the Red Stick force concentrated on the Tallapoosa River at Tohopeka (Horseshoe Bend). He first moved south along the Coosa River, about half the distance to the Creek position and established a new outpost at Fort Williams. Leaving another garrison, he then moved on Tohopeka with a force of about 3,000 effectives and 600 Cherokee and Lower Creek allies. The battle of Horseshoe Bend, which occurred on March 27, was a decisive victory for Jackson, effectively ending the Red Stick resistance.

The state of Georgia had a militia of perhaps 30,000. While the 6th Military District, consisting of both Carolinas as well as Georgia, had perhaps as many as 2,000 regulars. In principle, Pinckney could have mounted an offensive that would have ended the Creek war in 1813. However, efforts in this sector were neither as prompt nor as effective as they could have been.

In late November, Gen. John Floyd, with a force of 950 militia and 300–400 friendly Creek, crossed the Chattahoochee River and moved toward the Holy Ground. On November 29, he attacked the village of Auttose and drove the Creek from a strong position. After the battle, Floyd, who was severely wounded, withdrew to the Chattahoochee.

In mid-January, Floyd departed Fort Mitchell with a force of 1,300 militia and 400 friendly Creek for the village of Tuckaubatchee to await a link-up Jackson. On January 29, the Creek attacked his fortified camp on the Calibee Creek. Although the Georgian's repulsed the attack, Floyd and his militia considered this battle a defeat and retreated to Fort Mitchell, abandoning the line of fortified positions that they had created during their advance. This was Georgia's last offensive operation of the war.

In October, Gen. Thomas Flourney organized a force of about 1,000—consisting of the 3rd U.S. Infantry, militia, volunteers, and Choctaw Indians—at Fort Stoddert. Clairborne, ordered to lay waste Creek property near junction of Alabama and Tombigbee, advanced from Fort St. Stephen. He achieved some destruction but with no military engagement.

Continuing to a point about 85 miles north of Fort Stoddert, Clairborne established Fort Clairborne. On December 23, he encountered a small force at the Holy Ground and burned 260 houses. William Weatherford was nearly captured during this engagement, but was able to escape. Because of supply shortages, Clairborne withdrew to Fort St. Stephens

On August 9, 1814 the Creeks were forced to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which ceded 23 million acres—half of Alabama and part of southern Georgia—to the U.S. government. With the Red Stick menace subdued, Jackson was able to focus on the Gulf coast region. On his own initiative, he invaded Spanish Florida and drove a British force out of Pensacola. He next defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans. In 1818, Jackson again invaded Florida, where some of the Red Stick leaders had fled, an event known as the First Seminole War.

As a result of these victories, Jackson became a national figure and eventually rose to become the 7th President of the United States in 1829.